The City University of New York (CUNY) Haitian Studies Institute, directed by Dr. Marie Lily Cérat, held its annual three-day symposium on the Kreyòl language from Oct. 31 to Nov. 2 at Brooklyn College’s Student Center.

The centerpiece day was Nov. 1 when there were eight hours of guided discussions and presentations, shared lunches, music, and lectures on Kreyòl’s revival, moderated by CUNY Graduate Center’s Katia Henrys with the participation of Kreyòl translator Faidherbe “Fedo” Boyer.

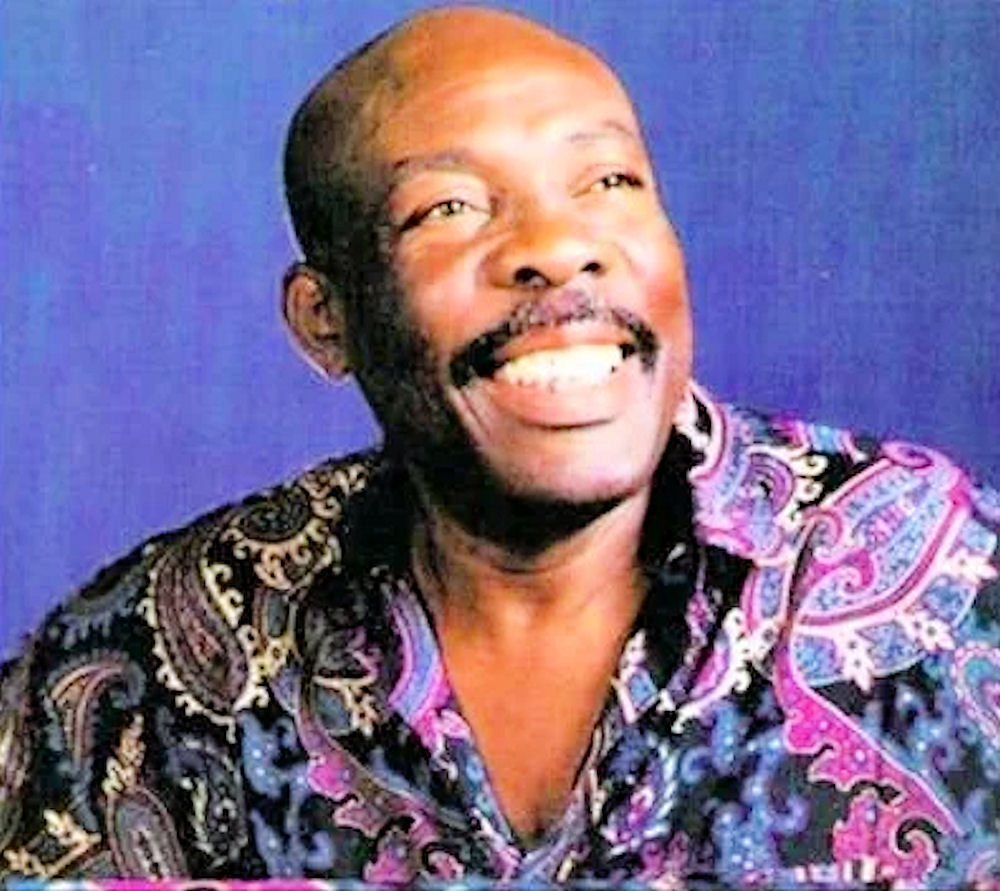

The symposium’s main theme was an exploration of the social, cultural, and artistic significance of the renowned Haitian soccer player, singer, guitarist, and bandleader Coupé Cloué, or (in Kreyòl) Koupe Kloure, who would have celebrated his centennial this year. Coupé Cloué was born Jean Gesner Henry on May 10, 1925 in Léogâne, Haiti, and he died on Jan. 29, 1998 in Port-au-Prince, only one month after his retirement from performing.

For the academics, artists, and activists who attended the symposium, Coupé Cloué played a key role in influencing Kreyòl’s revitalization.

Haitian-American students attend Brooklyn College in large numbers – many from the “Little Haiti” neighborhoods surrounding the school – so the organizers decided to hold the entire conference in Kreyòl.

By focusing on Haiti’s musical heritage, the conference sought to promote a deeper understanding and acceptance of Kreyòl in the diaspora. According to one conference participant, Guy Valovsky Mathieu, Kreyòl tends to be neglected in diaspora families’ homes (unlike in past decades), leading parents and grandparents to try to learn English from the upcoming younger generation.

Mathieu expressed the hope that Kreyòl (not English) will one day become the primary language of Haitian-Americans, even those not born in Haiti, and suggests that continuing the yearly conference organized by the Haitian Studies Institute would contribute to this goal.

“Celebrating Kreyòl culture is essential,” Mathieu said, asserting that there is growing academic curiosity and curriculum engagement with the language.

Kreyòl’s importance is elevated when researchers like Websder Corneille and Guy Petit-Frère publish theses on Coupé Cloué’s work, highlighting the language’s power, Mathieu said.

At the Nov. 1 session, Natalie Anantua performed a selection of Coupé Cloué’s compositions on the piano, reminding us of the singer’s rigorous legacy.

Nazaire Joinville, a doctoral student at Canada’s University of Sherbrooke, offered a firsthand account of how Kreyòl enriches and contributes to linguistic intelligence. The after-effects of colonialism, he argued, have hindered Kreyòl’s linguistic progress, leading some, to this day, to associate the language with ignorance and illiteracy.

Fifty years ago, Kreyòl was absent from the academic curriculum in Haitian schools. But in 1979, Education Minister Joseph Claude Bernard proclaimed Kreyòl the official language of Haiti’s educational system, and, in 1980, Kreyòl was integrated into schools. In 1983, Kreyòl was recognized by the Duvalier regime as one of Haiti’s official languages, and on Mar. 27, 1987, the Haitian government decreed that Kreyòl would be put on an equal footing with French. Presidential speeches began to be delivered in Kreyòl, starting with President Jean-Bertrand Aristide in 1991. Since then, the language has been widely integrated into schools, and baccalaureate exams are now administered in Kreyòl.

However, these steps have been slow and challenging, making Kreyòl’s equality with French still incomplete. For instance, children still learn and speak French in many schools but converse in Kreyòl at home. While French colonies Martinique and Guadeloupe struggle to integrate Kreyòl into their cultures, tiny La Réunion has taken many important, crucial steps toward adopting Kreyòl, Joinville said. Haiti’s Education Ministry should continue to adopt a consistent approach in making Kreyòl more official, and initiatives like the “Academic Kreyòl” program, launched in Haiti in 2012, has further consolidated progress made since 1979.

All prejudicial belittling of Kreyòl should be entirely abandoned in the Haitian educational system, Joinville concluded, and Haitian parents in the U.S. and Canada should encourage and teach Kreyòl to their children at home, not simply default to the language of the nation where they live as expats.