Overview:

Zohran Mamdani was elected mayor of New York City Tuesday with the backing of key Haitian American neighborhoods, marking a historic victory and signaling growing political power within the diaspora.

By The Associated Press | Additional editing and reporting by The Haitian Times

NEW YORK — Neighborhoods home to some of the largest Haitian American communities in New York City helped power Zohran Mamdani to a historic victory Tuesday night, as the 34-year-old assemblymember was elected the city’s first Muslim, South Asian and African-born mayor.

In Flatbush, East Flatbush, Canarsie, East New York, Jamaica, and Hollis — neighborhoods long anchored by working-class Haitian families — voters delivered double-digit margins in favor of Mamdani, a democratic socialist whose campaign emphasized affordability, immigrant protections and solidarity with marginalized communities.

Mamdani carried Flatbush by 57 points, East Flatbush by 25, Canarsie by 24, East New York by 21, and Jamaica by 27, according to early returns published by The New York Times.

An estimated 183,000 Haitians call the five boroughs home, with significant numbers living in central and south Brooklyn and southeast Queens. Demographers have said that about one-third, an estimated 57,000, are U.S. citizens who make up an engaged electorate that votes regularly.

Tuesday night’s results confirmed what many Haitian organizers predicted last month in a Zoom meeting hosted by Assemblymember Rodneyse Bichotte Hermelyn, where community leaders — many who had first supported challenger Andrew Cuomo in the Democratic Primary— laid out strategies to mobilize voters behind Mamdani.

“While being with him through the churches and the streets of Flatbush and working with community members, he definitely resonated with them,” Bichotte Hermelyn said. “He has listened to them, and it’s been with sincerity.”

Other Haitian American elected officials, including Assemblymember Phara Souffrant Forrest and Council Member Farah Louis, also endorsed Mamdani after the Democratic primary, citing his promises to defend immigrant rights and lower the cost of living.

“We are not asking for a lot,” Forrest said during the October meeting. “What we are asking for is a life of dignity — and now we’re going to make it happen together. Zohran is for us.”

A commanding win

Mamdani defeated former Gov. Andrew Cuomo and Republican Curtis Sliwa in a high-turnout race, with more than 2 million ballots cast — the largest in over five decades. With roughly 90% of the vote counted, Mamdani held a 9-point lead over Cuomo.

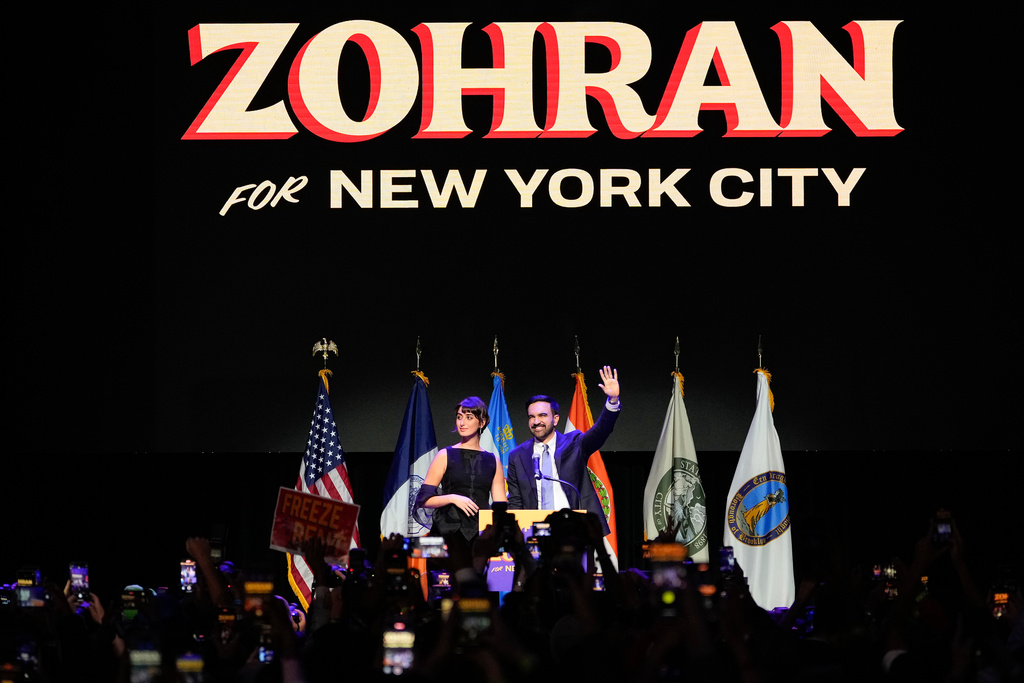

The mood at Mamdani’s victory party in Brooklyn was jubilant. Supporters cheered, waved the New York City flag and danced to reggaetón and konpa as The Associated Press called the race.

Cuomo, speaking at a subdued event in Manhattan, conceded with a warning: “Almost half of New Yorkers did not vote to support a government agenda that makes promises that we know cannot be met.”

Still, he offered to help Mamdani transition into office. “Tonight was their night.”

The Haitian vote: Organized and energized

From making an appearance at Michael Brun’s Bayo show in Brooklyn this summer to standing with TPS advocates in Little Haiti, Mamdani began outreach to the young and the worried in Haitian communities early on. Continuing his grassroots ground game, organizers canvassed neighborhoods like Canarsie, Flatbush, East Flatbush and Queens Village, distributing translated materials in Kreyòl and French and building WhatsApp groups to share information.

“Access to information is everything in our community,” said one attendee during October’s strategy session. “There can be great programs, but if we don’t know about them, we can’t benefit.”

Mamdani’s campaign team said those concerns were being addressed through multilingual outreach and partnerships with community-based organizations.

Louis noted Mamdani’s outreach across Caribbean communities, where he promised to protect Haitian immigrants from ICE raids and include culturally responsive policies in City Hall.

What’s next for City Hall?

Mamdani takes office Jan. 1 and has promised an ambitious agenda that includes:

- Free citywide bus service

- Free child care

- Rent freezes

- A new Department of Community Safety to respond to mental health crises

- City-run grocery stores in food deserts

He will face pressure from centrist Democrats, including Gov. Kathy Hochul, who opposes his plan to raise taxes on the wealthy to fund his proposals.

His stance on policing will also be closely watched. Mamdani, who once called the NYPD a “rogue agency,” has since apologized and pledged to keep the current police commissioner in place.

National figures have already weighed in. President Donald Trump, who previously threatened to cut federal funds to the city if Mamdani won, posted “…AND SO IT BEGINS!” on Truth Social Tuesday night.

In his victory speech, Mamdani addressed Trump directly.

“New York will remain a city of immigrants, built by immigrants, powered by immigrants — and now, led by an immigrant,” he said. “If anyone can show a nation betrayed by Donald Trump how to defeat him, it’s the city that gave rise to him.”

A notable moment for Haitian American civic power

For the Haitian diaspora — long active in union organizing, education and immigrant justice — Mamdani’s victory marks continued progress in politics. Although Bichotte Hermelyn, who leads the Brooklyn Democratic Party, Louis and other prominent Haitian elected officials first supported the scandal-plagued incumbent Mayor Eric Adams, then Cuomo in the primary, they began boosting Mamdani over the summer.

Meanwhile, in addition to his mailing fliers and making high profile appearances, Mandani’s canvassers knocked on doors in multistory buildings to encourage turnout. Haitian voters responded, helping elect a mayor who has promised to reflect their priorities and protect their dignity.

As the Zoom meeting closed last month, organizers created a ‘Haitians for Zohran’ WhatsApp group to coordinate voter outreach through Election Day. With Mamdani’s win now official, many are preparing to hold him accountable — and ensure Haitian voices are represented in City Hall.

“This is not just about a win,” said Louis. “It’s about building a city where our communities are finally seen.”